By Meg Friel

Executive Editor

“Again?”

Students, faculty and staff overwhelmingly responded to the news of white supremacy stickers being posted around campus, with an echo of incidents they have seen before.

St. Michael’s College and colleges in the surrounding area woke up the morning of Saturday, September 28, to stickers posted across campus from the white supremacy group, Patriot Front, boasting phrases such as “Reclaim America,” or “Keep America American.” This is the second time in recent years that white supremacist messages have emerged on campus. In February 2018, students found flyers posted on campus with messages saying, “It’s okay to be white.” This time, the stickers spread across campus left messages like, “Not Stolen, Conquered,” with an image of a map of the U.S. The stickers were removed immediately, says Doug Babcock, head of Public Safety, but students of color were shaken.

While these incidents were traced back to outside groups who came onto campus and also posted to other campuses in the area, many students say that microaggressions and racism occur in classrooms and in residential halls, leaving some students feeling unsafe on their own campus.

“People couldn’t sleep alone,” said co-president of the MLK Jr. Society Adrienne Rodriguez ‘21 of the 2018 incident. “We needed a buddy system. There was a group of like, 10 minorities, and we went around and took the flyers down.”

In response to the stickers incident this month ,the administration sent two emails to students, and held a community discussion on Friday Oct. 4 at 12:15, the day before October break began. About 40 students, faculty, staff and administration sat in Eddie’s Lounge, with chairs to spare. Students aired their frustration of the timing and date of the discussion, as many students had already left for their long weekend.

“I think it’s a great thing that they’re holding this meeting but listen, it’s been a week, this should’ve been done Monday. Now we’re having a meeting on Friday, but that’s when everybody’s leaving. At 12:15, who’s going to go?” Rodriguez asked.

“It just feels like nobody really cares what we’re going through,” she said. “This weekend, President Sterritt didn’t reach out to me. There’s only so much that one whole school email can do. Like, come talk to us. Come to the center [Center for Multicultural Affairs]. Show us that you care.”

President Lorraine Sterritt was present at the meeting, chiming in that “one student feeling unsafe is one student too many.” However, concrete plans as to what the administration will be doing to protect student’s safety are yet to be announced.

“With regard to students’ daily life on campus, we continue our quest for inclusion by listening, communicating, educating, and raising awareness,” Sterritt wrote in an email. “The administration cares very deeply about all our students. We want all of our students to be safe and to feel safe; to be respected and to feel respected.”

Dawn Ellinwood, Vice President for Student Affairs, chose to have the meeting on Friday as she didn’t want to postpone the meeting until after fall break.

“I wanted to gather people together to support, listen and support one another,” Ellinwood said. “I wanted the discussion to happen prior to October break and preferably earlier in the week, but I could not make it happen.”

Some students said this year’s response mimics what they saw in 2018, not only from the administration, but from the community of Saint Michael’s as a whole.

“The culture of the campus allows for those things to happen, and there’s not going to be some sort of uproar, or call for response,” said Marlon Hyde ‘21. “Everybody’s not going to immediately band together and say ‘Hey, this is wrong.’ People know that that isn’t going to happen here, especially when it comes to racism, because it doesn’t affect everyone equally.”

While the stickers demanded attention, more common microaggressions — subtle discriminations against members of a marginalized group such as a racial minorities– happen every day, Hyde said. They usually go unnoticed.

Student Safety, A Priority

Rodriguez describes Halloween of 2018, when she felt an act of discrimination was handled underwhelmingly by staff and administration.

“A student dressed up like a terrorist, wore a Muslim headdress, had an accent, a bloody axe, and wore the Koran in the other hand,” Rodriguez said. “I had multiple bias reports put in, like, in the teens. They sent him away for a weekend and moved him closer to where I’m living. They didn’t even tell him to take the costume off. He walked out of the student life office with it still on. I think that made all of my faith in the administration and public safety completely go away.”

Ellinwood said that staff works hard to try and eliminate these situations, even developing a Bias Response Team and protocol in order to try and immediately respond to situations such as these, and prevent them from happening in the future.

“Since I have been on campus, I have been working with a very dedicated group of staff and faculty on diversity, equity and inclusion on our campus,” Ellinwood said. “We have new systems in place because of this work, new systems such as the Bias Response Team and protocol. This work has been and needs to be continuous and I am dedicated to making sure our campus continues to move forward.”

The most recent published security report recorded nine race bias incidents in 2018, but only four were classified “determined.” Although these incidents are reported, students expressed at the community discussion that they feel that the topic of racial bias isn’t discussed enough.

“Student safety should always come first. Pub safe does absolutely nothing for people of color here,” Rodriguez said. “This administration just sweeps us under the rug. I get that we’re such a small percentage, but if you’re going to bring up diversity in the school, you need to freaking care.”

“I have heard students of color express their concerns and they relate other times and incidents that have also had significant effects and impacts on their feelings of safety,” Babcock said. “Many of those incidents and concerns are outside of Public Safety’s sphere of influence. We are one part of the campus, and we have our work to do, but all other areas of the college are also engaged in educating and addressing these issues for us to truly make progress.”

Microaggressions — the subtle racism

Some students of color say they experience small acts of racism and microaggressions on campus every day. Research done by the psychology departments at Marquette University and Victoria University shows a link between microaggressions and increased levels of depression and trauma among minorities.

“I was in a meeting yesterday, and we were talking about filling a position on campus,” said Associate Professor of Media Studies, Journalism, and Digital Arts Traci Griffith. “Someone else in the meeting asked where we were advertising and if we were hoping to attract diversity candidates. The response to that was, ‘Yes, we’re advertising, but we really want to make sure we get someone who’s qualified,’ – as if someone who is a diversity candidate is not qualified. There’s this element of, we need to justify, or qualify, this group of people. Those kinds of things happen all the time.”

“It’s sad to say, but it’s kind of the Saint Mike’s experience,” Hyde said, mentioning that he experiences microaggressions frequently. “Nobody cares about race or racism until an event like this happens, that’s our culture. The one thing that makes us talk about race is when we have these incidents.”

Politics and racism on campus

“I know a lot happened the last election year, so I’m kind of worried for next year,” said co-president of the Diversity Coalition Connor Vezina, ‘22. “I heard personal incidents where someone wrote ‘Trump’ on someone’s door because they were a person of color. It’s scary. This is supposed to be a place that’s safe for everyone, but that’s just a violation.”

“We like to tell ourselves that St. Mike’s is this warm, welcoming community and that people rally around each other in times of trouble and that we’re so open and welcoming to difference in our community, and I think in a large part that’s true, but I think that some people don’t always have that experience.”

“I feel the most for the students, particularly for the first years, who may not have experienced this in years past,” Griffith said.

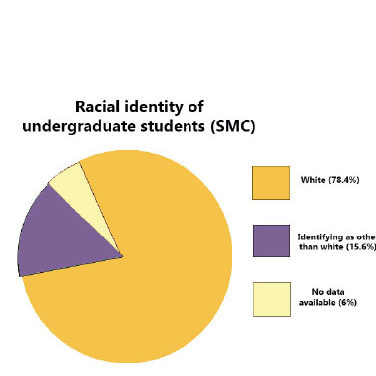

In 2018 the full-time instructional staff at Saint Michael’s was reported to be 90 percent white, according to The Integrated PostSecondary Education Data Systems report, or IPEDS. Out of 94% of undergraduate students for which the school has race and ethnicity data, only 15.6% of those classified as a race or ethnicity other than white.

“It’s so noticeable how white this campus is,” Hyde said. “It really hits you in the face. You start to realize certain things as you go year by year. When you’re in the room, what type of music that they play vs. when you’re not in the room. Why is it that when I’m there, it’s hip hop, R&B, Drake? When I’m there, it’s a little more slang, a little more of an urban language, but when I’m not there, it’s a totally different tone.”

Microaggressions range from subtleties such as these, to students being blatantly called the n-word.

“That’s why I don’t go to parties anymore (because people call me the n-word),”said co-president of the MLK junior society Jaron Bernire, ‘21. “I only say the n-word to my black friends because we’re all black. But when I hear a white person say it, I’m like, ‘Come on. Where’s the education there?’ I have to deal with race so much more here than I did in high school. Like, three times more.”

What happens inside the classroom

People of color at Saint Mike’s feel these microaggressions extend from outside of their campus culture to inside the classrooms. From the lack of diversity within faculty, to racial bias from faculty and students, these concerns contribute to the feeling of disclusion for minorities on campus.

“Sitting in the classroom is already more than enough to realize that, this is kind of lopsided,” Hyde said. “But when topics come up, and you yourself kind of realize, ‘I might be the only one that really understands this topic on a deeper, much more personal level.’ If we’re talking about race, even if nobody looks at you, you feel like the target is on you.”

“I think I’m targeted,” Bernire said. “I’m the only black person in all of my classes, or there’s only one other minority in other classes. Whenever we talk about race in class I’m like, ‘Jesus Christ, what are these people going to say?’ I’m scared to speak up in class. I feel like that’s what the teachers and the administration wants us to do, [teach students about their race]. When I leave, they have to make the next group of black people do that. It’s just a cycle.”

Some students and faculty of color still feel as though race isn’t brought up enough in the classroom, and even when it is, it’s often not well handled.

“A lot of times in the classroom, professors and other students expect students of color to speak on behalf of all people of color, which is an unfair place to be put in,” said Vanessa Bonebo ‘21. “I don’t think that all teachers know how to handle acts of racism and discrimination in the classroom, they just brush it off. I think faculty needs to be retrained on how to handle these situations.”

Students say they often feel used for marketing, however, once they’re accepted to Saint Michael’s, they’re left in the dark.

“I feel like this school wants more money than to help out the students more,” Bernire said. “Like, you’re trying to put black or hispanic people on the brochures just to get people to come, but as soon as you get us, past orientation, they’re like, ‘We don’t have to worry about them anymore.’”

In an effort to correct this, an “engaging diverse identities” requirement was added to the LSC curriculum, and the administration is actively working to bring in faculty of color.

“If you can count the faculty of color on two hands, that’s a problem,” Griffith said. “But that’s Vermont, so I don’t know that the expectation is any different. I think we try, and I think it’s gotten better in that we definitely have more classes that address things other than Western European culture. We have an “engaging diverse identities” requirement in the curriculum, so I think we’re working at trying to decentralize or at least expand our sphere of education.”

Vezina believes that white faculty, staff, and administration may be unaware of their oblivion to microaggressions due to their lack of experience around race.

“I know they do trainings, but I think it takes a lot of personal experience to catch and understand things,” Vezina said. “I think they lack in experience because this school is predominantly white.”

“There are faculty and staff members that care about students of color very deeply, but as a whole, I’m not sure that Saint Mike’s really takes us into consideration,” said Bonebo. “We’re just a number to boost diversity, not like they actually care about us being here. ”

In order to fix the problem, administration must recognize the problem, says Vezina. Students of color can no longer stand on their own on these issues of race and microaggression.

“Part of the work that needs to be done is helping develop the tools to confront and address these situations as they occur in the world,” Babcock said. “We (as a campus) continue to push Saint Mike’s to be better and set the example in many areas but problems will still exist in the world beyond our borders.”

“I don’t think the problem comes from them being white, I think it comes from their lack of awareness,” Vezina said. “They’re white, so it doesn’t affect them in the way it does to us. I can’t fault them for it, but I wish they were more aware and more willing to speak on these matters. Everyone needs to have a voice in this situation, or nothing will change.

“It can’t just be the people of color. We’re not enough people.”